New Report: The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’s Extractive Industries

My colleague, J.R. Mailey of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, just published The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’s Extractive Industries. Full disclosure: I haven’t read the report in its entirety, but I’ve seen J.R. brief on this topic and know the investigative and analytical work that went into producing it, so I’d highly recommend reading it. A summary is below:

With more than 20 countries possessing bountiful oil and mineral deposits, Africa is home to more resource-rich states than any other region in the world. If accountably governed, natural resource wealth could be a boon to a society, enabling valuable investments in infrastructure, human capital, social services, and other public goods. Yet, living conditions for most citizens remain dismal as a result of inequitable distribution of resource revenues. Natural resource wealth is also strongly associated with undemocratic and illegitimate governance. Roughly 70 percent of the world’s resource-rich states are categorized as autocracies. This pattern is not a coincidence. The steady flow of natural resource revenues funds the patronage and security structures these governments rely on to remain in power without popular support. Nearly without exception, Africa’s resource-rich states also exhibit high levels of public sector corruption. States heavily reliant on the export of oil and minerals, moreover, face a greater risk of civil conflict than their resource-poor counterparts.

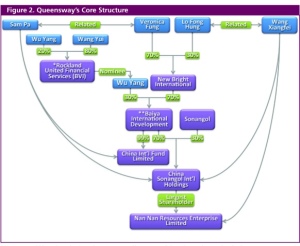

This report examines these linkages by tracking the practices of one group of investors that has been particularly active on the continent since the early 2000s: a Hong Kong-based consortium known as the 88 Queensway Group. Cultivating relationships with high-level government officials in politically isolated resource-rich states through infusions of cash, promises of billions of dollars in infrastructural development, and support for the security sector, Queensway has been able to gain access to major oil and mining concessions across Africa. Starting in Angola in 2003, Queensway has been engaged in the extractive industries in at least nine African countries, including Guinea, Madagascar, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.

Contracts—often in the billions of dollars—between Queensway-affiliated companies and African governments are rarely made public. The syndicate’s leaders have forged deals found to be unfavorable to the respective countries as a whole by appealing to the short-term interests of those senior officials controlling their countries’ natural resources. Queensway’s collaborations with the governments of Africa’s resource-rich states have often failed to improve citizens’ living standards. Promised high-profile infrastructure construction projects regularly fail to materialize. Allegations of corruption among senior government officials who control natural resource contracts are widespread. Reputable extractive firms are cut out of the market, undermining the long-term health of the resource sector. And unaccountable governments are able to persist, propped up by the infusion of financial and material support to the regimes in power.

Queensway’s business model persists in Africa and elsewhere because of weaknesses in domestic and international oversight structures. First, at the national level, predatory investors operate in environments where the institutions needed to hold public officials and international corporations accountable are often absent. Second, failure by the governments of countries of origin (“home countries”) to regulate the overseas activities of corporations anchored in their jurisdictions helps these firms escape scrutiny. Third, the international legal and institutional framework for dealing with corruption and exploitation in the extractive industries by multinational corporations is deficient. The use of anonymous shell companies anchored in these jurisdictions prevents outsiders—potential business partners, banks, regulators, and law enforcement officials—from identifying who truly controls and benefits from the operations of unscrupulous corporations.

You can find the full text of the report here: http://africacenter.org/2015/05/the-anatomy-of-the-resource-curse-predatory-investment-in-africa%E2%80%99s-extractive-industries/

Comments on President Obama’s Africa trip & US-Africa relations published in Think Africa Press

Today, President Obama kicks off his second visit to Africa as since becoming president, and will be visiting Senegal, South Africa, and Tanzania over the course of the next week. Accordingly, Thomas Tieku, Mwangi Kimenyi, Cobus van Staden, Witney Schneidman, and I are featured in Think Africa Press’ Experts Weekly: What Next for US-Africa Relations?

My comments in particular refer to the emphasis the Administration placed before the President’s visit to the continent in 2009 on including Ghana in a multi-region tour that included Russia and the G8 in Italy to demonstrate that Africa was ‘not a world apart, but a part of our interconnected world.’ (See the reference to this concept in the full text of his July 2009 Ghana speech). Four years later, this emphasis has been lost. Check out the rest of what I have to say about the significance of the President’s visit, as well as the contributions of my colleagues!

Guest Post – AFRICOM’s Impact on International and Human Security: A Case Study of Tanzania

This is a guest post by Mikenna Maroney, a MA Candidate in International Security at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies. She is currently a David L. Boren Fellow in Tanzania studying Swahili language and conducting research for her MA thesis on AFRICOM. Ms. Maroney seeks additional contacts with expertise on Tanzanian security policy, and can be reached for comment at mikenna.maroney@gmail.com.

U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) was established in 2008 due to growing awareness of Africa’s strategic significance to U.S. interests and international security. AFRICOM was presented as a new type of combatant command that would address traditional and human security threats through a pioneering interagency approach and structure, in addition to partner capacity building. AFRICOM would integrate significant numbers of personnel from the State Department, USAID, and other interagency organizations. U.S. officials asserted this would allow the command to address the root causes and, ultimately, prevent conflict and instability.

The creation of AFRICOM, the complexity of its mission, and the threats present in the region give rise to questions regarding AFRICOM’s impact in executing U.S. national security policy in Africa, addressing human security issues, and its ability to foster a positive image of itself and U.S. national security policy. To explore these issues, my Master’s thesis research is a case study of Tanzania. I chose Tanzania as a case study on AFRICOM because I felt that it is an often overlooked actor in the East African security environment. I was also interested in examining how AFRICOM currently engages with African states not engaged in an ongoing conflict and its ability to foster bi-lateral relations with a state that has, at times, had a strained relationship with the U.S.

While often overshadowed by neighboring states Tanzania’s long-standing stability, history of mediating regional conflicts (most notably the Burundian civil war), contributions to peacekeeping missions, and hosting of regional and international organization such as the East African Community (EAC) and International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), make it an important actor in the often volatile East Africa region. Yet Tanzania faces similar threats as its neighbors including illicit narcotic trafficking, piracy, and terrorism. Tanzania also faces pervasive threats to human security. As one of the world’s poorest countries, economic development fails to reach the majority of the population, resulting in poor health and education systems, as well as the world’s 12th highest HIV/AIDS infection rate.

A strategic U.S.-Tanzanian relationship is critical for countering the threats Tanzania faces and bolstering the country’s capacity to address ongoing regional conflicts and humanitarian crises. This research seeks to answer three questions: What is the impact of AFRICOM in executing U.S. national security policy in Tanzania? How and to what extent has AFRICOM addressed the conditions of human insecurity? Does AFRICOM foster a positive public perception within Tanzania?

The initial findings have shown that Tanzania extensively engages with AFRICOM through its security cooperation programs and exercises. Former AFRICOM Commander Gen. Carter Ham singled out this partnership in his recent remarks to the Senate Armed Services Committee stating, “We are deepening our relationship with the Tanzanian military, a professional force whose capabilities and influence increasingly bear on regional security issues in eastern and southern Africa and the Great Lakes region.” Indeed, Tanzania’s contribution of troops to the recently authorized UN offensive combat force in Eastern Congo illustrates the important peace and security role the country plays in the region and the necessity of its military having the capacity to fulfill this role.

In terms of how and to what extent AFRICOM addresses Tanzania’s human security issues, this research has found the command’s activities fit those of a more traditional combatant command; emphasizing military-to-military partner capacity building and engagement. While many of AFRICOM’s programs (MEDCAP, Partner Military HIV/AIDS, Pandemic Response, and VETCAP) focus on human security related issues, they are directed at the Tanzanian military. Regarding public perceptions, Tanzanians have more knowledge and interest than I was led to believe would be the case with public opinion of AFRICOM oscillating between negative and neutral.

Tanzania faces significant security threats both internally and regionally. Although these initial findings have not found that AFRICOM is addressing human security issues in the broader population, AFRICOM is building the Tanzanian military’s capacity to address and prevent instability and conflict, serving Tanzanian, regional, and U.S. security interests.

Key questions for African-initiated intervention force for eastern DRC

On August 7th and 8th, International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) heads of state met to discuss the deployment of an international force to fight the M23 rebel movement that has been active in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) North Kivu region since April of this year. While they did not end up reaching a consensus on an intervention force, I still thought I’d attempt to think through the kind of questions that would need to be answered to establish such a force.

- What would the mission be? Like the current discussions the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is having about a regional intervention force for Mali, it will be essential for regional stakeholders to articulate what their objectives are and what their concept of operations might be in order to attain said objectives. Will they be focusing on fighting M23, or will they also be addressing instability caused by the Raia Mutomboki? Would this force attempt to address the underlying causes of the ongoing conflict in North Kivu, which could be a long-term commitment that would surpass a purely military intervention? Would this force focus on protecting civilians while allowing the Armed Forces of the DRC (FARDC in French) to deal with rebel groups? Starting to answer these types of mission-oriented questions would be a prerequisite for obtaining African Union (AU) and United Nations (UN) mandates, which could facilitate international support – which gets to my next question.

- Who would pay for this deployment?Troop-contributing countries (I’ll get to who they might be in a minute) would need to determine whether they can afford to pay the salaries of the units they would deploy, the use of (or acquisition of) contingent-owned equipment during the deployment, the transport of military assets to the eastern Congo, and the maintenance of these assets in the field. (I’m sure I forgot something, but you get the picture.) If troop-contributing countries cannot foot the bill, then the AU, UN, European Union (EU), United States would need to be willing and capable of providing financial assistance – either on a bilateral basis or on a multilateral basis – which gets to my next question.

- What framework would be used for an intervention force? The UN already has just under 20,000 military and police personnel as part of the UN Organization and Stabilization Mission in the DRC(MONUSCO), but it is possible that the UN (and the AU for that matter) are overtasked, both globally and in the DRC itself. Therefore, we might be looking at a sub-regional organization taking the lead akin to what ECOWAS is attempting to do in Mali. Unlike the situation in Mali, however, the DRC is not a member of a sub-regional organization that has a functional security component with a precedent for regional military intervention. The DRC is a member of both the Economic Community of Central African States (CEEAC in French) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and these sub-regional organizations are supposed to have regional brigades that would fall under the African Standby Force (ASF). However, I don’t know whether the SADC Standby Force Brigade (SADCBRIG) or its CEEAC equivalent, the Central African Multinational Force (FOMAC in French), would be willing and capable of leading an intervention force. Therefore, if there is no sub-regional organization that has an established military component is able to take the lead, then how would this intervention force be comprised?

- Who would the players be? Since we don’t know whether a sub-regional organization or a multilateral coalition of countries would intervene in the DRC, it’s difficult to ascertain which countries could be part of this notional force. But since the ICGLR is talking about such a force, we’ll start with their members: Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the DRC, Kenya, Rwanda, Sudan (not sure if South Sudan is a member), Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. If I were compiling an intervention dream team from these members, I would want Angola, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda on my team. Why these and not the others? Off the top of my head, these countries have reasonably professional militaries with proven warfighting capabilities, are active in AU and UN peacekeeping operations (with the exception of Angola), and have countries stable enough that deploying soldiers abroad would probably not inhibit their armed forces from addressing other national security threats. That said, many of these countries have baggage in the DRC as a result of their involvement in the 1998-2003 civil war (Angola, Rwanda, and Uganda), or more recently, alleged support for M23 (ahem…Rwanda). Also, would these countries even be interested in intervening? I would say Rwanda would because of the threat it perceives from the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR). Angola’s participation would depend on the extent to which its security is affected by events on the opposite side of the Congo, as well as the extent to which the ruling People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA in Portuguese) feels more comfortable keeping the military at home in case there is instability surrounding this month’s elections or to contain additional protests by civil war veterans. And while I don’t think Kenya has baggage in the DRC, I doubt that instability in North Kivu is compelling enough to deploy the Kenya Defence Forces (KDF) there when their focus is really on Somalia. Thus, the militaries that might be the most capable of fighting M23 in North Kivu may either fail to be perceived as a neutral force or their countries lack a compelling reason to get involved. As a result, an intervention force might have to look further afield to get troop contributors or make do with less capable forces.

So I guess the bottom line is that I don’t think an intervention force will come to fruition for the eastern Congo due to some of the issues I’ve raised above.

You must be logged in to post a comment.