How might Burundi’s political instability affect its integrated military?

After weeks of protests against Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza’s intent to seek a third term, a cabal of military officers launched a coup on 13 May. Although the coup ultimately failed, it laid bare divisions within the military, which had thus far remained neutral. This development raises the question of how the political dispute over the president’s eligibility to seek a third term might impact the cohesiveness of Burundi’s military, integrated in the aftermath of the country’s 12-year long civil war.

Military integration is a peace-building strategy that involves incorporating or amalgamating armed groups into a statutory security framework as part of a transition from war to peace. According to Roy Licklider in New Armies from Old: Merging Competing Military Forces after Civil Wars, military integration is an increasingly common mechanism to include in peace agreements. Between 2000 and 2006, 56% of civil war settlements included provisions for integration, compared with 10% of all agreements in the 1970s.

The military integration process in Burundi was a product of the Pretoria Protocol on Political Defence and Security Power Sharing and the accompanying Forces Technical Agreement, signed in October 2003. These agreements complemented the 2000 Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement, and stipulated that all armed groups were to be disarmed and integrated into the army and police force.

Burundi’s current political instability highlights the importance of three aspects of the country’s military integration process, which could test the cohesion of the force amidst this crisis:

- The Use of Quotas

In “Perils or Promise of Ethnic Integration? Evidence from a Hard Case in Burundi,” Cyrus Samii found that the Burundian military operates as a deeply integrated and cohesive institution at the macro levels as a result of the imposition of ethnic quotas during the process of military integration. The Arusha Accords established the concept of 50% Hutu-50% Tutsi quotas in the military in order to overcome the country’s history of coups and ethnic conflict. In addition, the top officer echelon would have 60% (Burundi Armed Forces) FAB and 40% Congress for the Defense of Democracy Forces – Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD), with the margin between these quotas to be made up with Hutu members of the FAB, combatants of other armed political parties, and new recruits. Samii furthermore concluded that, at the micro level, the contact that resulted from integration reduced the prejudices and ethnic salience among former combatants. This is contrary to the findings he cited from the field of social psychology, that such a method could intensify or “freeze” conflicting ethnic identities.

Favorably, the group of military and police officers that attempted to overthrow Nkurunziza was multi-ethnic, and included insiders from the president’s party, the CNDD-FDD. Meanwhile, the military has not yet fractured according to ethnic lines or civil war era armed group affiliations, which may be an indication that imposing quotas on the security forces has prevented the military from being more disruptive in a time of political uncertainty.

- Political Power-Sharing Arrangements

Burundi’s transition from war to peace included both military and political power-sharing arrangements. In “Civil War Settlements and the Implementation of Military Power-Sharing Arrangements,” Matthew Hoddie and Caroline Hartzell argue that military integration can only succeed as part of a wider peace-building initiative. Likewise, in “Rebel—Military Integration and Civil War Termination,” Katherine Glassmyer and Nicholas Sambanis suggest that political and military power-sharing provide mutually reinforcing assurances, thereby increasing the success of a military integration process. In the context of Burundi, the president’s attempt to seek a third term has arguably weakened the political pillar of these arrangements.

In February, Nkurunziza dismissed the leader of last week’s coup, General Godefroid Niyombare as head of intelligence for advising him against seeking a third term. Although Niyombare’s coup ultimately failed, it has indicated divisions in the military that are tied to how the force sees its role as a protector of the Arusha accords and the constitution. In fact, former Defence Minister Pontien Gaciyubwenge had affirmed earlier this month that the military would not take any actions that would undermine the Arusha accords and the constitution. He was sacked on Monday, in a cabinet reshuffle that also included the Ministers of External Relations and Commerce. With the erosion of political power-sharing in the spirit of the Arusha accords, it may be increasingly likely for the integrated military to disintegrate, thereby confirming the aforementioned hypothesis on the relationship between political and military power-sharing arrangements.

- Military Efficacy and Cohesion

As military integration is implemented concurrent to other peacebuilding measures, it is difficult to isolate the specific effects of the process in order to determine its success or failure. However, in New Armies from Old, Licklider attempts to designate factors that could indicate the success or failure of an integration process. One is military efficacy, which is the extent to which the new military can perform tasks or remain integrated in peacetime. In the context of Burundi, the military’s ability to contribute to regional peacekeeping operations as Nina Wilén, David Ambrosetti, and Gérard Birantamije detail in “Sending Peacekeepers Abroad, Sharing Power at Home: Burundi in Somalia,” demonstrates that the process has been successful this far, according to Licklider’s criteria. Other indicators suggested by Licklider and applied to the case of Burundi would be whether the military is subject to civilian control when ordered into use against domestic opponents, and whether the integration has made the resumption of large-scale violence less likely. Like the use of quotas and the erosion of political power-sharing arrangements, the fallout from the failed coup and fears of reprisals against the media and protesters will test the efficacy and cohesion of the Burundian military. Indeed, as protests resumed in parts of Bujumbura on Monday, it was the military that supplanted the police in restoring order to the capital city – the first time they had played this role since protests began last month. Furthermore, amid reports of thus far non-violent conflict within the military as to whether to use force to suppress the protesters, the Deputy Chief of Defence Staff had to be called in to prevent the confrontation from escalating.

A decade after the end of its civil war, Burundi’s military has been considered a successful case of military integration, especially in contrast to attempts at military integration in the Eastern Congo and South Sudan. However, how the military fares in the coming weeks and months could provide important data on what factors cause militaries integrated during war-to-peace transitions to subsequently disintegrate.

Trying to understand the protests and attempted coup-iny in Burundi

Perhaps you’ve been following the weeks of protests in Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi, against President Pierre Nkurunziza’s intent to run for a third term and the subsequent attempted coup-iny (no one quite knows what to call it, so I combined coup & mutiny) of 13 and 14 May. If you’re like me and are struggling to understand what exactly is going on in the runup to legislative and elections originally scheduled for May, June, and July I’d recommend consulting four sources that will give you a sense of recent developments & reference other valuable sources:

- The Washington Post’s Monkey Cage Blog (@monkeycageblog) posts on Burundi.

- #BurundiSyllabus: Context for the Current Crisis by @SarahEWatkins

- Timeline of Events in Burundi by @DHirschelBurns

- Burundi: Key Actors and Speculative Musings by @ethuin

It sounds like all of these sources will continue to be updated as the situation unfolds, so definitely keep your eye on them.

New Report: The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’s Extractive Industries

My colleague, J.R. Mailey of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, just published The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’s Extractive Industries. Full disclosure: I haven’t read the report in its entirety, but I’ve seen J.R. brief on this topic and know the investigative and analytical work that went into producing it, so I’d highly recommend reading it. A summary is below:

With more than 20 countries possessing bountiful oil and mineral deposits, Africa is home to more resource-rich states than any other region in the world. If accountably governed, natural resource wealth could be a boon to a society, enabling valuable investments in infrastructure, human capital, social services, and other public goods. Yet, living conditions for most citizens remain dismal as a result of inequitable distribution of resource revenues. Natural resource wealth is also strongly associated with undemocratic and illegitimate governance. Roughly 70 percent of the world’s resource-rich states are categorized as autocracies. This pattern is not a coincidence. The steady flow of natural resource revenues funds the patronage and security structures these governments rely on to remain in power without popular support. Nearly without exception, Africa’s resource-rich states also exhibit high levels of public sector corruption. States heavily reliant on the export of oil and minerals, moreover, face a greater risk of civil conflict than their resource-poor counterparts.

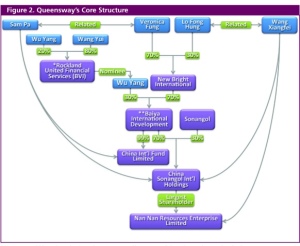

This report examines these linkages by tracking the practices of one group of investors that has been particularly active on the continent since the early 2000s: a Hong Kong-based consortium known as the 88 Queensway Group. Cultivating relationships with high-level government officials in politically isolated resource-rich states through infusions of cash, promises of billions of dollars in infrastructural development, and support for the security sector, Queensway has been able to gain access to major oil and mining concessions across Africa. Starting in Angola in 2003, Queensway has been engaged in the extractive industries in at least nine African countries, including Guinea, Madagascar, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.

Contracts—often in the billions of dollars—between Queensway-affiliated companies and African governments are rarely made public. The syndicate’s leaders have forged deals found to be unfavorable to the respective countries as a whole by appealing to the short-term interests of those senior officials controlling their countries’ natural resources. Queensway’s collaborations with the governments of Africa’s resource-rich states have often failed to improve citizens’ living standards. Promised high-profile infrastructure construction projects regularly fail to materialize. Allegations of corruption among senior government officials who control natural resource contracts are widespread. Reputable extractive firms are cut out of the market, undermining the long-term health of the resource sector. And unaccountable governments are able to persist, propped up by the infusion of financial and material support to the regimes in power.

Queensway’s business model persists in Africa and elsewhere because of weaknesses in domestic and international oversight structures. First, at the national level, predatory investors operate in environments where the institutions needed to hold public officials and international corporations accountable are often absent. Second, failure by the governments of countries of origin (“home countries”) to regulate the overseas activities of corporations anchored in their jurisdictions helps these firms escape scrutiny. Third, the international legal and institutional framework for dealing with corruption and exploitation in the extractive industries by multinational corporations is deficient. The use of anonymous shell companies anchored in these jurisdictions prevents outsiders—potential business partners, banks, regulators, and law enforcement officials—from identifying who truly controls and benefits from the operations of unscrupulous corporations.

You can find the full text of the report here: http://africacenter.org/2015/05/the-anatomy-of-the-resource-curse-predatory-investment-in-africa%E2%80%99s-extractive-industries/

You must be logged in to post a comment.